Suspension Compression: Impact Absorption and Geometry Adjustment

When suspension compresses, its primary function is to absorb the impact. However, it also plays a significant role in steepening the geometry of the bike. This dual purpose ensures a smoother ride while maintaining the desired positioning of the bike.

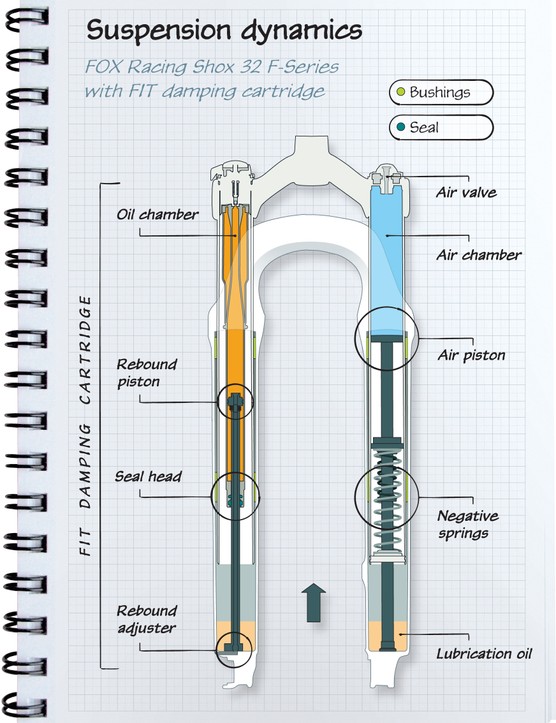

Forks: Damping and Compression Cartridges

It’s important to note that not all forks have dedicated legs for damping and compression cartridges. However, a majority of them do. These legs, either left or right, house the necessary components for managing the damping and compression, allowing for a more controlled and responsive suspension system.

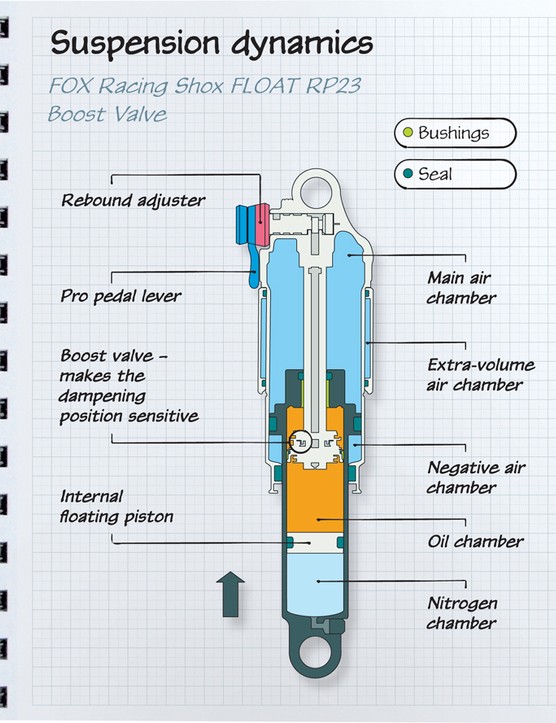

Fox’s Float RP23: The Reliable Workhorse

Considered the go-to choice for most full suspension bikes on UK trails, Fox’s Float RP23 shock proves its reliability time and time again. With its impressive performance, this shock enhances the riding experience by providing optimal suspension capabilities.

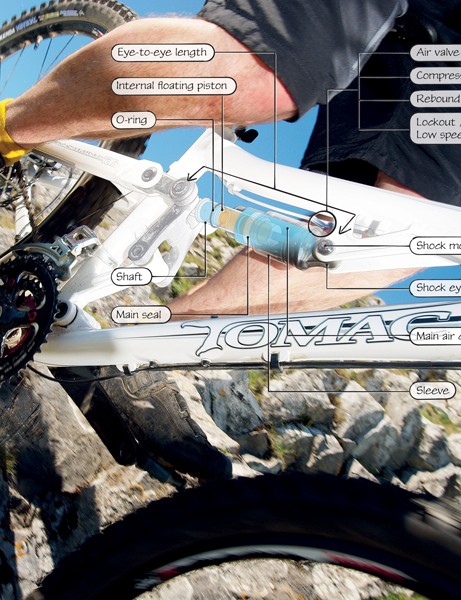

Variety in Shocks, Consistency in Anatomy

Shocks may come in various eye-to-eye lengths and offer different options, but their fundamental anatomy remains unchanged. Regardless of the specific model or specifications, the core components and principles of shock design and functionality remain consistent.

**Fork Components**

**Headline 2: Evolution of Suspension in Mountain Bikes**

Before the widespread adoption of suspension in the late Nineties, mountain bikes were known for their bone-shaking rides. The old rigid-forked, rigid-framed bikes were thrilling on rough tracks, but they left riders grimacing and their eyeballs rattling in their sockets.

When suspension was first introduced, many riders dismissed the initial designs as ugly, heavy, and inefficient. However, times have changed. Modern suspension bikes offer the ability to ride faster and longer on uneven surfaces while reducing the impact and strain on your body. They smooth out rough landings and come to your rescue when you find yourself in deep waters.

**Headline 2: The Role of Suspension in Bike Performance**

Suspension serves two crucial functions in a bike: improving traction by keeping the wheels in contact with the ground as much as possible and cushioning the impacts encountered on rough terrain. However, if the suspension is not properly set up, even a great bike can feel like riding on a mattress, holding you back. Once you dial in the settings for your fork and/or shock, your riding skills will take a significant leap forward.

Suspension mainly comes in two forms: coil sprung or air sprung, although low-cost forks may still utilize elastomers. All suspension systems incorporate compression and rebound damping to control the speed at which the fork or shock moves through its travel and returns. While cheaper shocks and forks may lack external adjustments, it is now common for suspension systems to have at least external rebound controls.

**Headline 2: Optimizing Suspension for Terrain**

Effective suspension allows the wheels to seamlessly follow the contours of the terrain, allowing them to drop into hollows and navigate around rocks and bumps. To achieve this, suspension is set up with sag, which means your weight on the bike determines the bike’s position within the available travel. Typically, sag is set between a quarter and a third of the total travel.

Most forks and shocks share a similar construction: a smaller tube that slides inside a larger tube, with the spring and damping system positioned inside. Telescopic forks, consisting of two upper legs (stanchions) connected by a crown, slide in and out of a one-piece lower leg construction (sliders).

While most forks have separate legs for housing damping and compression cartridges, not all forks follow this design. Rear shocks, on the other hand, are scaled-down versions with a single leg. Coil shocks have the coil spring positioned externally, rather than inside the shock (coil-over shock). As the fork or shock is compressed, it compresses the spring medium, storing the energy and releasing it during rebound. Damping plays a crucial role in dissipating this energy and finely controlling the suspension’s behavior during compression and extension.

Fox Anatomy

Fox’s Float RP23 shock is the workhorse for most full suspension bikes on the UK trails. It is known for its reliability and performance. The chassis of this shock is designed to provide smooth and efficient suspension movement.

Chassis

When it comes to forks and shocks, there are various options available in terms of shape and size to suit different applications and riders. However, it is important to be aware of the standards that may or may not be compatible with your setup.

Fork and Shock Compatibility

Rear shocks are relatively easier to match with your frame as they require precise measurements such as shock eye-to-eye length, shock stroke, and specific fitting hardware. On the other hand, forks have a range of differences. Modern fork steerer tubes come in three different diameters: 1 1/8 inches, 1.5 inches, and tapered from the latter to the former. The compatibility of these fork options depends on the size of your head tube and headset.

Consider Tapered Steerers

Tapered steerers have emerged as a recent development that combines the stiffness of the 1.5-inch width at the crown with compatibility with standard 1 1/8-inch stems. This allows for increased stiffness without a significant increase in weight. However, fitting tapered steerers requires a tapered head tube or a special headset.

Axle Options

Just like forks, there are also several types of axles to consider. Most forks come with 9mm quick-release (QR) dropouts, which is a carry-over from road bike technology. However, screw-through or through-axle forks are becoming increasingly popular due to their reduced flex. These forks require specific hardware and a compatible hub.

Screw/Bolt-Through Axles

The two main standards for screw/bolt-through axles are 20mm and 15mm. Some hubs can be converted between these sizes, and even from quick-release. Additionally, the trend of thicker and wider stanchions has contributed to increased fork stiffness, allowing for more precise steering, less twisting, and reduced braking flutter. However, these advancements come with an added weight penalty.

Travel

The travel of a fork or shock refers to the total available compression, typically ranging between 80mm and 200mm (3-8 inches). More travel enables a softer spring rate and gives the fork or shock more time to absorb impacts, ultimately enhancing control over energy absorption. The necessary amount of travel depends on the intended use and the bike’s geometry. It is important to consult the manufacturer before fitting new suspension to ensure warranty validity and avoid adverse effects on the bike’s handling.

Springs

When it comes to springs, there are various options available to suit different preferences and riding styles. The choice of spring should be based on the specific requirements of your bike and your personal preferences. It is advisable to consult with the manufacturer to determine the best spring option that will not compromise your warranty or negatively affect your bike’s performance.

The spring is responsible for storing the energy created during the compression of the shock or fork. In cross-country forks, the spring is typically compressed air or a metal coil. Air springs offer precise adjustments for the rider’s weight and are lightweight, but they can suffer from stiction (when the stanchions don’t slide smoothly in the lower legs due to flex in the fork) and increased resistance from sealing.

Unlike a coil spring, the spring rate of an air spring increases as the fork compresses. This is known as progressive suspension, which can cause the fork to become stiffer towards the end of its travel. Coil springs have adjustable preload to set the ride height and sag, but the adjustment range is usually narrow, often requiring a change of spring to achieve desired results.

Damping

An undamped fork or shock would simply release the stored energy in the spring and send it back towards you. Control is crucial, and to achieve that, oil is forced through ports and shims inside the stanchions to slow down the movement.

Rebound damping, as the name suggests, controls the speed at which the fork or shock extends after compression, converting excess energy into heat as the oil passes through valves. Most forks and shocks have an adjustable rebound dampening to precisely tune the speed of rebound. Too much dampening can cause the fork or shock to pack down over repeated impacts, while too little can result in an uncontrolled and bouncy feel.

Compression damping governs the fork or shock’s reaction as it compresses, allowing it to respond proportionally to impacts of different sizes. Slow-speed damping controls movements like brake dive, fork bobbing, and excessive compression in berms, while high-speed damping prevents the fork or shock from bottoming out on big hits and drops.

However, excessive high-speed damping can lead to problems. Oil pressure may build up, causing a sharp knock when the oil can’t quickly pass through the ports or shims. Advanced forks and shocks have shim stacks, which are thin washers that bend out of the way, facilitating faster oil flow and movement of the fork or shock.

Lockout levers prevent the fork or shock from moving, with some options allowing a small amount of travel to maintain traction. Lockout is particularly useful on smooth climbs or road sections. Blow-off adjusters enable riders to set the force required to unlock the lockout and regain full travel. While not all forks and shocks incorporate these features, at the very least, rebound damping is necessary.

Jargon buster

Suspension fork terminology

- Adjustment dial(s): Also known as top caps, these components not only allow for external adjustments such as compression, rebound, threshold, and travel adjustment but also seal the top of the stanchions/air springs.

- Air valves: Depending on the fork, these valves can be for the main or supplementary air springs, the negative air spring, or the platform damping adjustment valve. Keep them clean and ensure the valve core is tightened to avoid leaks.

- Axle: This refers to the type of axle used, such as a regular 9mm quick-release, 20mm bolt-through, or 15mm bolt-through. More recently, quick-release bolt-through axles like RockShox’s Maxle and Maxle Lite (20mm and 15mm for 2011 forks) and Fox’s QR15 (15mm) have become increasingly common on cross-country and trail bikes.

- Bushings: These synthetic slider guides enable smooth telescopic movement between the upper and lower legs of the fork.

Crown:

The crown refers to the “hips” that hold the fork stanchions and attach to the steerer tube. It plays a crucial role in the overall stability and performance of the fork.

Dropouts:

Traditionally, forks used slotted 9mm dropouts for quick-release hubs. However, with the emergence of new 15/20mm through-axle standards, compatible forks now have a hole instead of a slot to slide the axle into. This design change enhances the strength and durability of the fork.

Fixing bolts:

Fixing bolts are extremely important components that secure the internal spring/piston rods in place. They also prevent damping oil from leaking out and ensure that the entire lower leg assembly stays intact.

Fork brace:

A fork brace, often in the form of an arch or a pair on certain brands like Magura or DT Swiss, serves the purpose of preventing the lower legs from moving independently. By effectively restricting torsional flex, it ensures optimal tracking and stability.

Lockout lever:

The lockout lever is a valuable feature that restricts oil and air flow through the compression or rebound circuits, effectively locking the fork in a rigid position. This functionality proves particularly useful when climbing or riding on flat terrain. Many lockout levers also come equipped with a blow-off valve, often adjustable, to protect against unexpected impacts that could potentially cause injury.

Negative spring:

The negative spring acts as a helper spring, opposing the main spring, to assist in overcoming seal resistance. This added support helps optimize the suspension performance of the fork.

Preload adjuster:

The preload adjuster allows for increasing the initial spring resistance of coil and elastomer forks. If you find yourself needing to make several turns to achieve the desired resistance, it may be a sign to consider opting for a higher spring weight.

Rebound dial:

The rebound dial serves as an external adjuster for the rebound damping circuit. Positioned either at the top of the fork leg or at the base, it is typically distinguished by its red color. By increasing the rebound damping, the speed at which the fork leg returns after each impact is slowed down. Conversely, decreasing the rebound damping enhances the speed of the fork leg’s return.

Remote levers:

Remote levers allow for convenient bar operation of one or more of the fork leg or crown mounted adjusters. This added flexibility enables quick and effortless adjustments while on the move.

Seals:

Seals play a crucial role in keeping the fork’s internals protected and free from dirt. Comprised of multiple wipers and lubricating sponges, they require regular cleaning and inspection to ensure optimal functionality.

Slider/lowers:

The slider or lowers, made of cast magnesium or carbon fiber, constitutes the moving part of the fork. In general, larger sliders translate to greater stiffness, making them ideal for freeride and aggressive trail forks. Conversely, skinnier sliders are typically lighter and offer more flexibility, making them suitable for cross-country forks.

Spring:

Springs are responsible for facilitating the fundamental up and down motion of a fork. They come in various types, including air, coil, elastomer, or a combination of all three. Each type offers unique characteristics such as adjustability, smoothness, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. Springs can be located in either one leg or both, depending on the fork.

Stanchion:

The stanchion acts as the slippery upper leg of the fork, enabling smooth movement of the lower leg. Commonly made of aluminum, occasionally steel, stanchions come in varying diameters ranging from 28 to 40mm. As the diameter increases, so does the stanchion’s stiffness and strength. It is important to be vigilant for any scratching or corrosion, as they can quickly compromise the integrity of the fork’s seals.

Steerer tube:

The steerer tube, typically made of aluminum or carbon to reduce weight, or steel to enhance strength and affordability, is responsible for connecting the fork to the bike’s frame. Steerer tubes come in different sizes, with 1-1/8in being the standard for cross-country bikes, and 1.5in steerers commonly used in freeride or downhill bikes. Tapered steerers, characterized by a taper from 1-1/8in at the top to 1.5in at the fork crown, have become popular for all-mountain and aggressive trail bikes, as they offer a balance of stiffness and lightness.

Travel adjuster:

Many manufacturers incorporate various travel adjustment systems to allow riders to alter the amount of travel on-the-go or when stationary. These systems prove beneficial in effecting geometry changes for climbing or descending. Depending on the system, the adjustment can be stepped (e.g., from 100mm to 150mm), incremental (e.g., 3mm per click), or infinite (providing free adjustment anywhere within the range of travel). Some forks even offer internal adjustment options, allowing riders to reduce a 120mm fork to 100mm of travel if desired.

Rear shock terminology

The terminology used when discussing rear shocks can be quite confusing for beginners. In this article, we will break down some of the key terms and phrases you need to know to better understand your rear shock.

Air valve:

One important component of air shocks is the Schrader valve used for adding or removing air from the positive air spring. This valve is typically marked with a ‘ ’ and should be kept clean. If you notice any leakage, make sure to check that the valve core is tight.

Bottom-out bumper:

To prevent a harsh clang when the shock reaches full compression, most shocks are equipped with a simple bumper known as the bottom-out bumper.

Coil:

Coil shocks feature a metal coil spring as their main suspension element. These springs can be made of steel or titanium for lighter weight. Additionally, coil springs can have different rates such as straight rate or rising/falling rate. The weight of the spring, measured in ft/lb, is typically printed on the side along with its dimensions.

Compression adjuster:

The compression adjuster is a dial or lockout lever that allows you to control the compression damping circuit of the shock. This is important for fine-tuning the shock’s performance according to your preferences and riding conditions.

Eyelet:

At either end of the shock, you will find a 6mm or 8mm hole called the eyelet. This serves as a mounting point for the shock and is an essential part of its design.

Length:

Shocks vary in length, and this measurement is taken from eyelet to eyelet. So, when referring to the length of a shock, it means the distance between the two eyelets.

Lockout / low-speed compression:

Some shocks are equipped with a lockout or low-speed compression feature. This damping circuit helps to resist compression from low-speed inputs, such as pedaling forces. It can greatly improve pedaling efficiency on smoother terrains.

O-ring:

An O-ring is a rubber ring located on the shock’s shaft. It serves as a visual indicator, showing the ‘tidemark’ and helping riders achieve accurate sag set-up. By observing the O-ring’s position when sitting on the bike, you can determine how much travel is being used.

Piggyback chamber:

This additional chamber, mounted parallel to the main body, is commonly found on long-travel air shocks used in all-mountain and downhill riding. It provides extra damping or air spring expansion, enhancing the shock’s performance in demanding terrains.

Preload collar:

Coil shocks feature a threaded collar known as a preload collar. This collar allows riders to add additional load to the spring, resulting in a stiffer start. If you find yourself using more than 2.5 turns from contact, it may be advisable to switch to a heavier spring.

Rebound adjuster:

The rebound adjuster controls the rate at which the shock extends after compression. It is often color-coded, with red being a common choice. However, some shocks may use different colors like blue, so it’s essential to consult your user manual for the correct identification.

Seal head:

Designed to prevent the insides from leaking out and the outside elements from getting in, the seal head is equipped with wiper seals. Regularly checking for any splits, embedded grit, or other damages is crucial to prevent any potential harm to the shock’s shaft. If your shock can be dismantled, make sure to clean it regularly.

Shaft:

The shaft is the moving part of the rear shock. It is typically made of cast magnesium or carbon fiber. In general, a larger shaft implies greater stiffness, making it suitable for freeride or aggressive trail riding. Conversely, a skinnier shaft indicates lighter weight and increased flexibility, making it more suitable for cross-country riding.

Shock mount:

The shock mount refers to the connection point between the shock and the bike frame. It is usually comprised of alloy spacers, although some shocks may use a spherical rose joint to reduce sideways stress. Regularly checking the width and looking out for wear or rattling is crucial, and any signs of damage should be addressed immediately.

Sleeve:

Acting as an airtight can, the sleeve contains compressed air that acts as a spring in some rear shocks. Certain sleeves are adjustable, allowing riders to change the shock’s travel or internal chamber dimensions, thereby influencing the shock’s rate of compression.